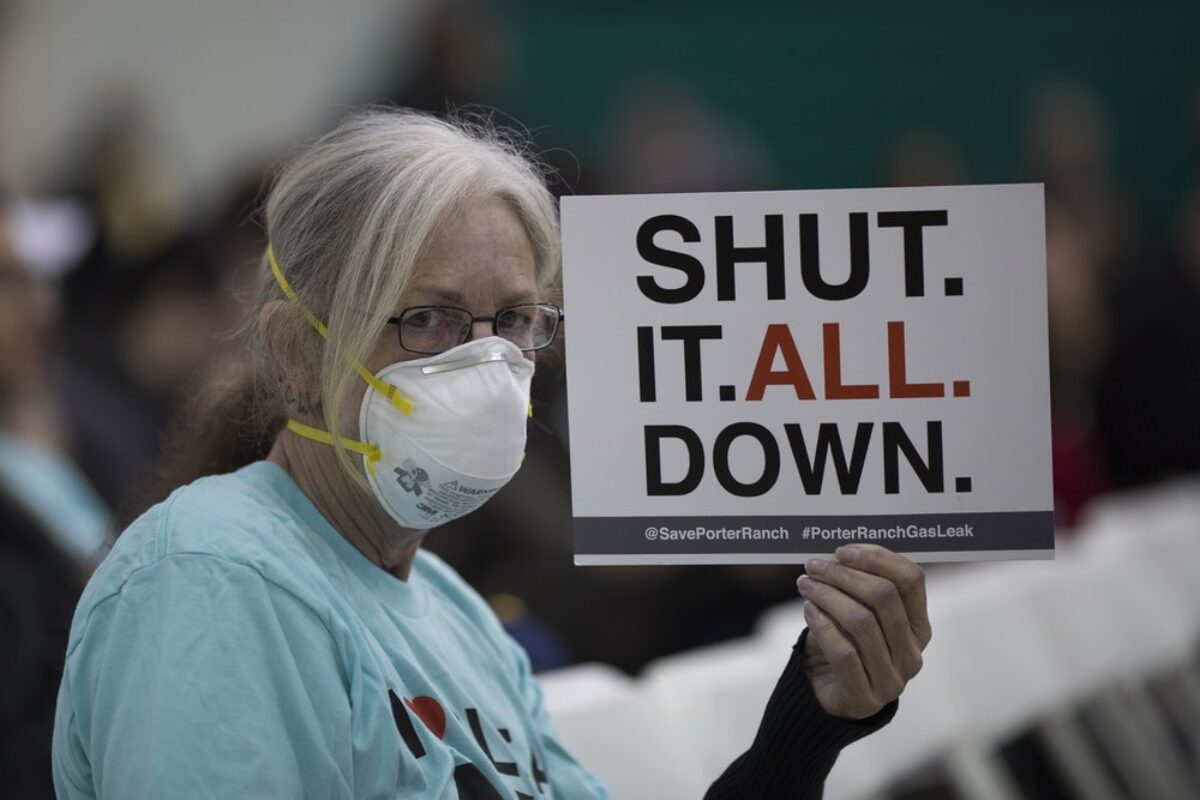

In October 2015, a fragile well casing ruptured at the Aliso Canyon natural gas storage field in Los Angeles, California—and no one could figure out how to stop it. For 118 days, 100,000 metric tons of methane and other hazardous pollutants seeped into the atmosphere. The single worst natural gas leak in American history was not only a disaster for the climate; it displaced thousands of nearby residents for months. Even after returning home, many complained of headaches, rashes, nosebleeds, and other symptoms they blamed on the lingering airborne chemicals.

And most of these people didn’t see it coming. The majority of residents near Aliso Canyon claimed they had no idea they lived near a natural gas storage field until the 2015 blowout happened. They didn’t know that if any of the wells ruptured, they were at risk of exposure to a host of toxic chemicals, which could cause serious neurological and respiratory problems and even certain kinds of cancer. They could also be at risk of death from a pipeline explosion, like the victims of the Colorado blast in 2017.

The massive Aliso Canyon storage field, which contained more than 110 underground wells, is just a small part of America’s much larger natural gas infrastructure. Approximately 15,000 such wells are active across the United States, and nearly half of them are concentrated in six states: Pennsylvania, Ohio, West Virginia, Michigan, New York, and California.

For the many thousands of Americans who live near these wells, as well as federal regulators who are tasked with keeping the public safe, these wells are out of sight, out of mind. And a new study shows their dangers to be far greater than previously believed.

Published Monday in the journal Environmental Health, Drew Michanowicz’s study was directly inspired by Aliso Canyon. After that disaster, he and his research team at Harvard’s T. H. Chan School of Public Health wanted to get a better idea of just how many people in America live near similar underground gas storage facilities.

After surveying the surroundings of more than 9,000 active wells in those six states, they found 6,000 located in suburban areas. Some 53,000 people live within 650 feet of a well, about 10,000 more people than previously estimated. The researchers found that most of those people had no idea about the threat lurking sometimes directly under their homes. “Because of suburban encroachment, some of these homes are sitting literally on top of these storage fields, especially in Ohio and Pennsylvania,” Michanowicz said. (For context, the closest home to the Aliso Canyon disaster was a mile away.)

This is especially worrying because most wells at underground storage facilities are more than 50 years old, and most were not even designed to store natural gas, Michanowicz said; his 2017 study estimated that one in five of these wells were built for gas production, not storage, and are thus likely to be missing subsurface safety valves and other equipment needed to store gas under high pressure. (Federal data released after that study also showed Michanowicz’s number was too conservative; two-thirds of these wells are being used in ways they were not intended decades ago.)

Failure to properly maintain wells can lead to disasters like the one in Aliso Canyon. The facility’s owner, Southern California Gas Company (SoCalGas), was accused in a May report of negligence for not repairing corroded pipes, and for not investigating dozens of smaller leaks dating back to the 1970s. “If there is nobody guaranteeing the safety of these other wells across the U.S., Michanowicz said, “tens of thousands of people don’t realize that they’re one corroded steel casing away from disaster.”

A study published in the June 26 issue of the peer-reviewed journal Environment International showed what such disaster looks like: The Aliso Canyon rupture released air pollutants including benzene, toluene, xylene, and other chemicals which can cause neurological problems, respiratory problems, and cancer. Now, many of Aliso Canyon’s neighbors, and Los Angeles County firefighters, are suing SoCalGas for health symptoms they believe were caused by the leak.

But a disaster such as Aliso Canyon’s doesn’t have to occur for nearby communities to be at risk. The June study’s senior author, UCLA Professor Dr. Michael Jerrett, said toxins could be seeping out of gas wells across the country every day, not just during catastrophic well blowouts. The leaks go undetected because few of the wells in the U.S. add mercaptan, a chemical that causes the distinct odor most associate with natural gas.

There are some protections in place. Setback rules, which are enacted by municipalities or states, forbid new oil and gas facilities from being built within a certain distance, typically 650 feet, of existing homes. But old wells are not subject to such rules, and no states, except Texas, have laws mandating that new homes can’t be built within a certain distance from existing wells.

“We are not saying immediately sell your homes if you live near these wells,” said the Monday study’s co-author, Kate Konschnik, director of the Nicholas Institute for Environmental Policy Solutions at Duke University. “But these facilities do need greater scrutiny than they’ve been getting. This is a manageable hazard, but that’s not the same as being managed.”

In the U.S. every year, 15 percent of the natural gas produced in the U.S. is injected back into the ground, into depleted oil or gas fields, aquifers, even salt caverns. These storage fields are used to manage fluctuations in customer demand; they inject gas into the wells during times of low demand, and withdraw it when demand spikes. Operators also store gas when the price is low, in the hopes of selling when the price is high.

The oil and gas industry maintains that these storage fields, from California to Pennsylvania, are needed for backup, to maintain energy reliability in the case of low supply or high demand. But the necessity of these fields has been disputed. In 2017, an independent report from a California engineering firm concluded that, in the Los Angeles region, storage fields like Aliso Canyon’s are not necessary to prevent blackouts.

But assuming these fields are necessary to energy security, a lot more could be done to ensure their safety, on both the state and federal levels. In California, for example, regulators haven’t recommended, let alone mandated, the closure of Aliso Canyon or any other gas storage facilities.

Federal protections are lagging, too. New rules issued by the federal Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration at the end of 2016 established minimum guidelines for underground gas storage but have not been finalized. Also in 2016, a Federal Interagency Task Force released 44 recommendations to regulators to help minimize future leaks, including phasing out the “single point of failure” wells like the one that ruptured at Aliso Canyon. But those recommendations don’t carry the weight of enforcement.

The federal Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act specifies natural gas facilities that need to engage with first responders in communities, as well as how to write emergency response plans, and conduct trainings. But only facilities that have “extremely hazardous substances” on site have to do this, and methane, which was released in vast quantities during the Aliso Canyon blowout, is not on that list. The Safe Drinking Water Act requires reporting about what’s injected into a well, but that law excludes underground wells.

And there is no federal regulation requiring monitoring of the air around the wells, nor have there been any studies about the health effects on people living near them. One such facility—Playa Del Rey, in the sprawling Los Angeles basin—contains more than half a million residents within a five-mile radius. It’s also in an area prone to seismic activity, just like Aliso Canyon, which puts the pipes at risk of rupturing. But the facility may already be causing harm. “We know from going door to door that many residents have been getting sick, and some have settled with the operator, SoCalGas, for damages,” said Alex Nagy, Southern California Organizer at the Los Angeles branch of Food & Water Watch. SoCalGas denies its facilities are sickening people.

Konschnik was hopeful that stricter regulations would be enacted after the Aliso Canyon disaster, but said that public pressure on the issue has subsided. “I hope there won’t be another Aliso Canyon to make states and the federal government regulate these structures,” she said. “But we are a country that reacts to disaster.” It may take a calamity much worse than the Aliso Canyon rupture to open public officials’ eyes.

By LARRY BUHL

July 8, 2019

Article original appeared at: https://newrepublic.com/article/154425/natural-gas-disaster-underground-storage-wells-suburban-america