The built environment is increasingly recognized as a major contributor to health outcomes. Environments that encourage walking while discouraging driving reduce traffic-related noise and air pollution – associated with cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, premature death, and lung function changes especially in children and people with lung diseases such as asthma. Quality, safe pedestrian environments also support a decreased risk of motor vehicle collisions and an increase in physical activity and social cohesion with benefits including the prevention of obesity, diabetes, and heart disease as well as stress reduction and mental health improvements that promote individual and community health.

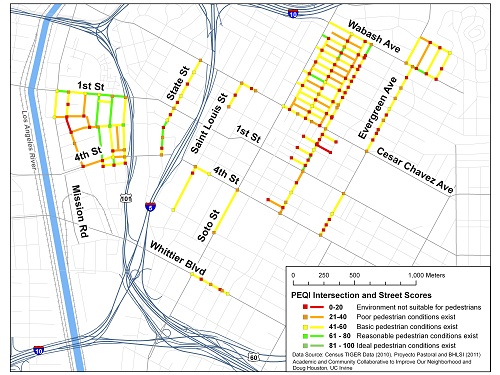

The Pedestrian Environmental Quality Index (PEQI) questionnaire was developed in 2008 by the San Francisco Department of Public Health Program on Health, Equity and Sustainability (SFPDH) to assess the quality and safety of the physical pedestrian environment and inform pedestrian planning needs. It evaluates the pedestrian environment in five categories (intersection safety, traffic, street design, land use and perceptions of safety and walkability).

In 2009, with funding from The California Endowment and the UCLA Center for Occupational and Environmental Health, UCLA adapted San Francisco’s PEQI tool for use in Los Angeles. In 2011, we translated the paper-survey form into a mobile phone application with automated scoring and web-based mapping, known as PEQI 1.0. Both paper and smartphone versions of PEQI 1.0 are available in English and Spanish, and have been used by several community groups and planning agencies.

From 2010-2012, SFDPH upgraded the questionnaire to version 2.0, based on up-to-date information available in transportation and public health journals on pedestrian safety, pedestrian comfort, and walkability. In addition, PEQI 2.0 was tested for inter-rater reliability, and changes have been made to improve the likelihood that two independent auditors would rate the same intersection or street segment in the same way.

By putting strong evaluative metrics into the hands of citizens and agencies alike, urban planning becomes democratized in whole new ways, allowing for prioritization of investments where they are needed most. Strong data is the basis for real change as we strive to redesign our cities to facilitate active transportation and physical activity, while simultaneously reducing the harms of pedestrian injury, motor-vehicle pollution and greenhouse gas emissions.

For information about the original PEQI, created by SFDPH, visit:

PEQI Methods & Indicators Manual (2008) and https://www.sfdph.org/dph/EH/PHES/PHES/Pastprojects.asp

PEQI 1.0 Reports and Resources

- Health Impact Assessment (HIA) Practitioners Training Presentation (2012) by Christina Batteate

- Taking Health to the LA Great Streets: Measuring Walking, Biking and Safety (2016) by Jimmy Tran

Below are reports produced specifically for the ACCION project (Academic-Community Collaborative to Improve Our Neighborhood) funded by The California Endowment. These reports were produced in a joint effort between UC Los Angeles, UC Irvine and the Boyle Heights community groups, Proyecto Pastoral and Union de Vecinos.

- Walkability & Pedestrian Safety in Boyle Heights: Summary (2011)

- Peatones Aumentando la Accesibilidad para Caminar en Boyle Heights (2011)

- Reintroducing the Pedestrian: A Handbook for Improving Walkability and Pedestrian Safety (2010) by Aleessa Atienza

- Walk On: Walkability Assessment in Boyle Heights, Los Angeles (2011) by Anqi Zhao

- Reintroducing the Pedestrian: A Case Study of Boyle Heights’ Efforts to Improve Safety, Health and Transportation (2010) by Aleessa Atienza

Other Southern California PEQI assessments have also been conducted, led by local agencies in Carson, Pasadena and San Diego.

PEQI 1.0 Training Materials

Materials for Conducting a paper-based PEQI 1.0 audit

- PEQI Data Collection protocol

- PEQI Training slides

Presentación del PEQI (español) - Intersection Form

Formulario del Intersección (español)

Intersection Form (coder’s version) - Segment Form

Formulario para un Segmento de la calle (español)

Segment Form (coder’s version) - Cheatsheet

Guía rápida (español) - Data Entry and Analysis Spreadsheet

- Segment Quiz

- Intersection Quiz

To view PEQI 1.0 mobile app visit: www.peqiwalkability.appspot.com

References

- Cutts, BB., Darby, KJ., Boone, CG., & Brewis, A. (2009). City structure, obesity, and environmental justice: an integrated analysis of physical and social barriers to walkable streets and park access. Social Science & Medicine, 69, 1314-1322.

2. Ewing, R., L. Frank, et al. (2006). Understanding the relationship between public health and the built environment. A report prepared for LEED-ND Core Committee, Design, Community & Environment, Lawrence Frank and Company: 137.

3. Gordon-Larsen, P et al. (2009). Active commuting and cardiovascular disease risk: the CARDIA study. Arch Intern Med, 169(13), 1216-23.

4. Hamer, M & Chida, Y. (2008) Active commuting and cardiovascular risk: a meta-analytic review. Prev Med, 46(1), 9-13.

Contact Christina Batteate cbatteate@ucla.edu for more information.