“People were dropping like flies,” said Dr Christy Montegut, his voice slowed by exhaustion.

Dr Montegut, the coroner in St John the Baptist parish, recited a scene of devastation similar to the ones seen by coroners in major metropolitan areas of the United States overwhelmed with Covid-19 deaths. But St John the Baptist, a small jurisdiction of 43,000 people in southern Louisiana, is no sprawling metropolis. Here, in this sparsely populated parish 30 miles from New Orleans, the Covid-19 death rate is the highest of any county in America with a population of over 5,000 people.

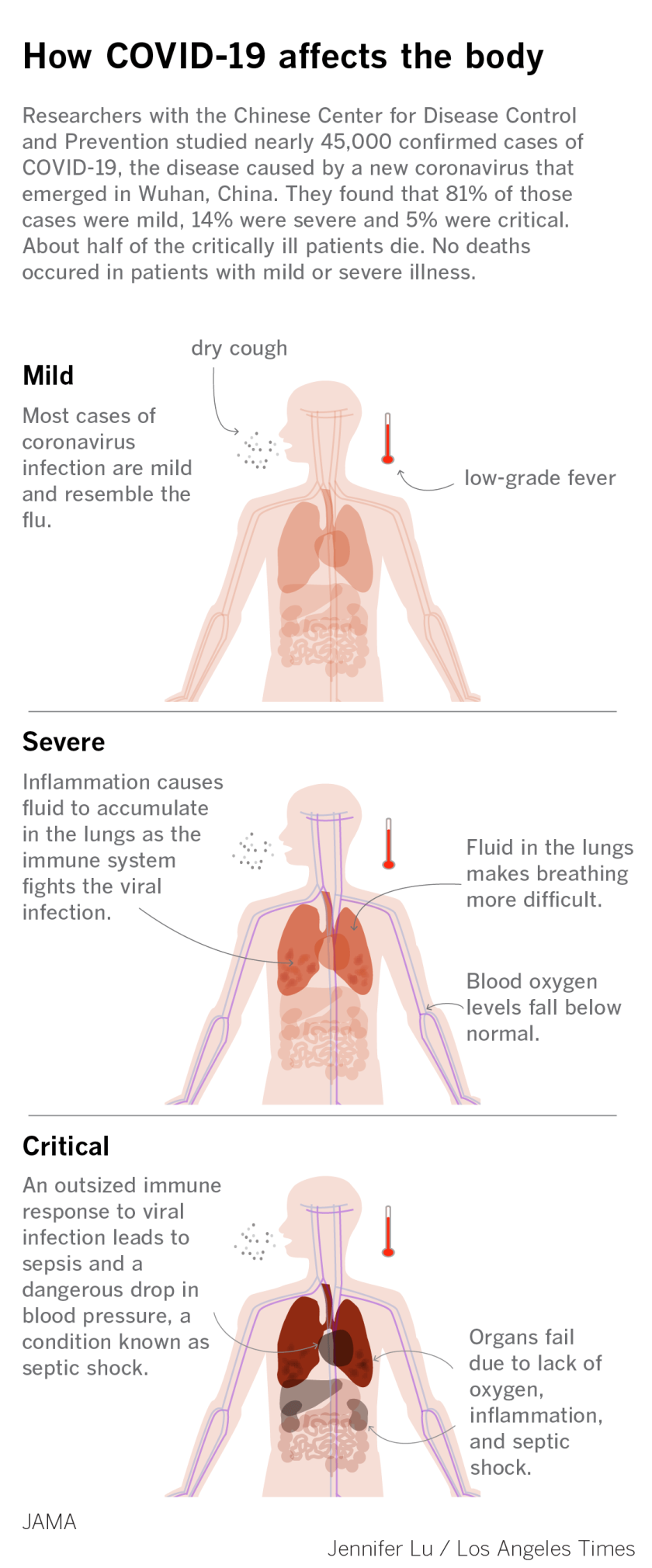

“We were getting calls almost every hour. The body count was just … amazing. …They all died in the same way. They got to a hospital, were on a ventilator, but the body just couldn’t keep going. They died in spite of full treatment. The virus is overwhelming.”

According to Montegut’s latest count, 30 people have died of Covid-19 in the parish since the outbreak of the crisis, a rate of 68.7 per 100,000 people. By contrast, New York City, the center of the virus in America, has a rate of 29.

The Trump administration is now tracking deaths in the parish along with other major urban hotspots in the country, Dr Deborah Birx, the US government’s coronavirus response coordinator, said at Sunday’s White House briefing.

Louisiana continues its battle with the virus. Governor John Bel Edwards announced on Monday that 512 people have died statewide and acknowledged for the first time that African American residents made up 70% of all deaths, despite being only 32.7% of the population.

The racial disparity was not immediately clear in St John the Baptist. But Montegut warned that if the death rate continues at the pace it has over the past 14 days, the parish will be completely overwhelmed. He has requested a refrigerated truck to store bodies. There is no morgue in St John the Baptist parish, nor are there any ventilators or a hospital, meaning all Covid-19 patients are being treated at facilities in other locations including New Orleans and Baton Rouge.

The coroner confirmed that eight deaths had occurred at a veterans nursing home in the town of Reserve, but fatalities have now been recorded in most towns throughout the parish. Most have been elderly residents with underlying health conditions.

“It gets depressing when you don’t see an end in sight,” Montegut, also a practicing family doctor, said. “And every day is just more bad news.”

Funeral directors in the parish have so far been able to keep up with the surge in deaths, but, said Geri Baloney, the owner of a funeral home in the town of Laplace, a continued outbreak will strain their resources.

Like other funeral homes, she has adjusted services to meet social distancing guidance. Tape on the floors guides mourners to stand eight to 10 feet apart during viewing processions, and she’s also started to offer online video streaming as an option to families unable to gather in person.

“It’s emotionally difficult,” said Baloney of the coronavirus crisis. “It’s a time that I tell everyone to be safe and cautious, but we have to be considerate and compassionate.”

In an indication of the depth of the crisis, the parish sheriff last week issued a nighttime curfew, one of the few jurisdictions in America to do so.

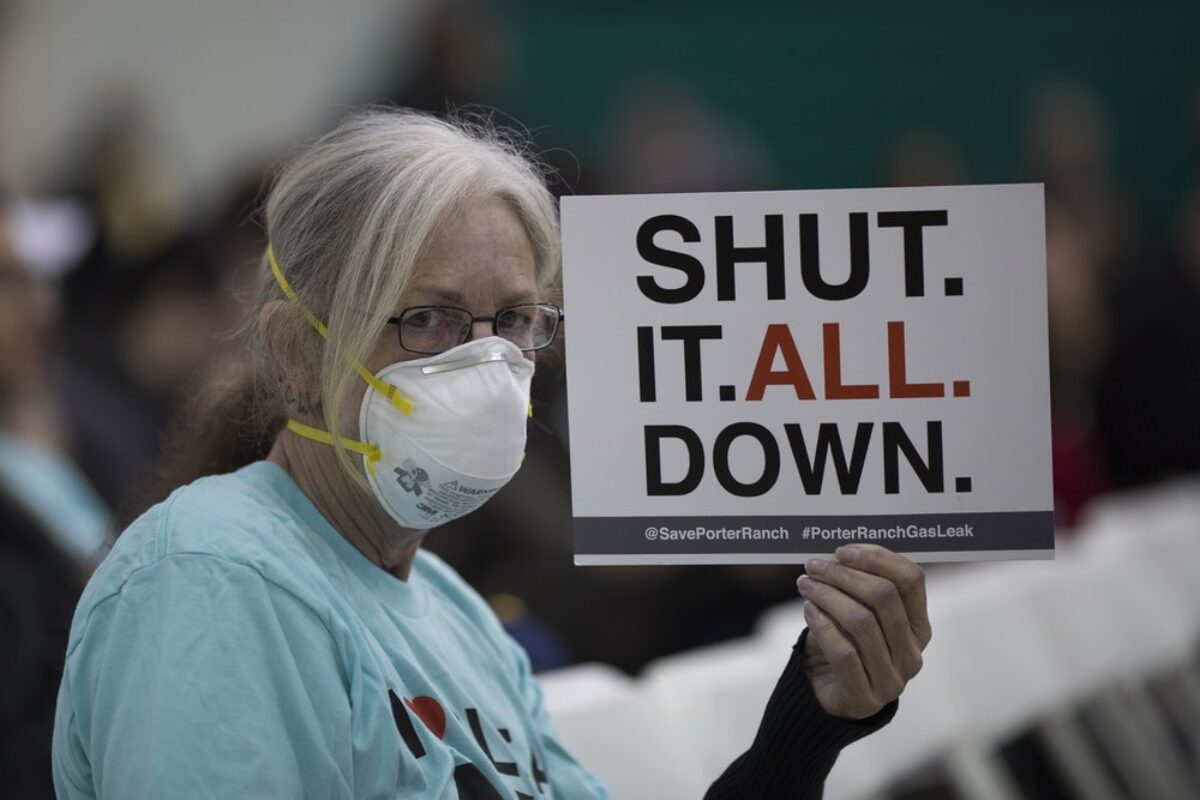

St John the Baptist has already commanded national and international attention due to major air pollution tied to a petrochemical plant operated by the Japanese firm Denka at the centre of the parish. Reserve is the subject of a year-long Guardian series, Cancer Town, and home to the highest risk of cancer due to airborne toxins anywhere in America, according to US government data.

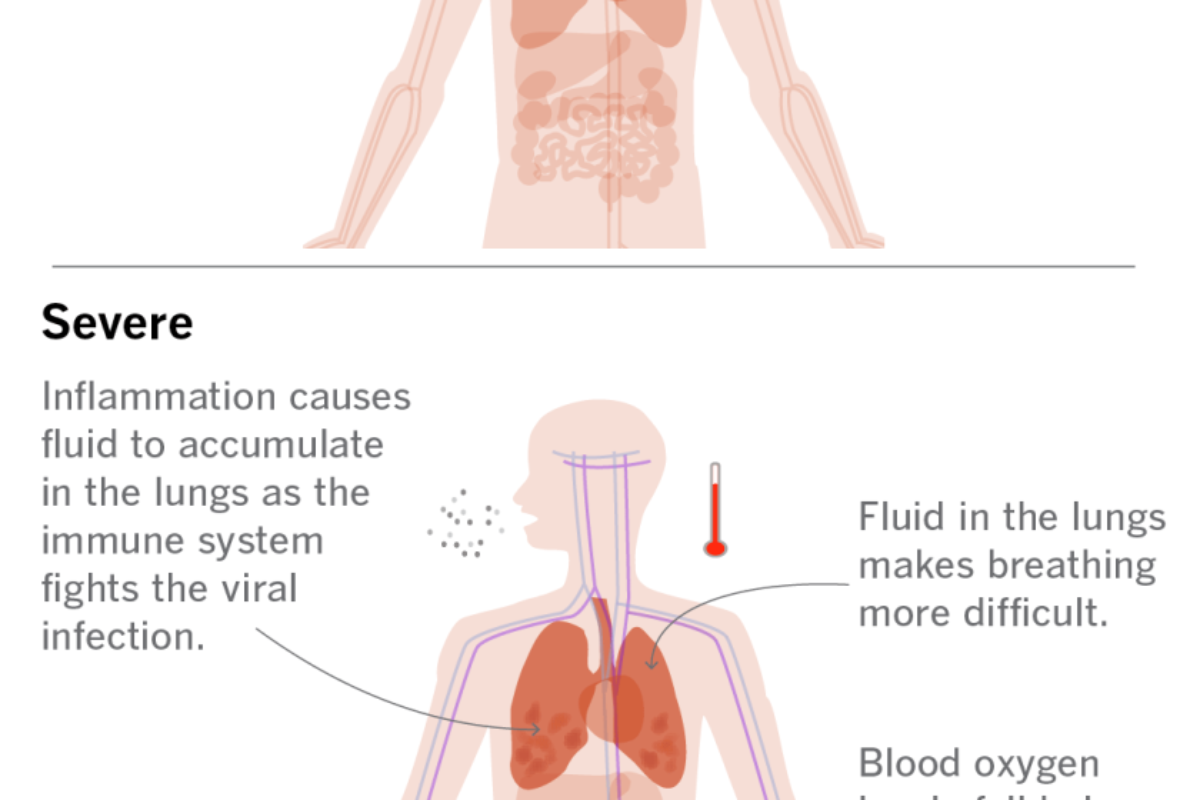

Residents living in Reserve voiced concerns that decades of air pollution places them at a higher risk of coronavirus fatality, since the virus attacks the lungs.

Robert Taylor, the director of the concerned citizens of St John, and a lifelong resident of Reserve, said a number of neighbours on his block, which sits a few thousand feet from the plant, have been hospitalised with Covid-19. One, according to Taylor, has died.

“It’s so hectic right now,” Taylor said. “It feels hopeless for us. People are dying every day and I don’t know what to do to protect myself.”

Wilma Subra, an environmental scientist and community advocate, shared Taylor’s concerns and added that the rest of the heavily polluted area between New Orleans and Baton Rouge, known as Cancer Alley, was primed for a disproportionate impact from coronavirus.

“The Denka facility has been releasing toxic chemicals into the air for 50 years. All the community have some type of respiratory impact, some more than others. But they’re already very vulnerable,” she said. “And then you add the exposure to the virus, which has a huge impact on the lungs, then they are much more apt to get it and then to have very detrimental effects.”

Dr Michael Jerrett, an environmental health sciences professor at the UCLA Fielding school of public health, studies the links between air pollution and disease. He says that since the coronavirus is new, it is too early to draw firm conclusions. But his past research has demonstrated that air pollution increases the risk of pneumonia, a disease similar to Covid-19.

“Being in areas of higher exposure to common air pollutants like nitrogen dioxide and fine particulate matter, does increase the risk of acquiring pneumonia. So to the extent that Covid behaves in a similar way to bacterial pneumonia, which is more common, or other viral pneumonias, we have evidence that long-term exposure well increases your susceptibility to acquiring the disease.”

The Denka spokesman, Jim Harris, argued there was no relationship between the plant’s emissions and an increased risk from Covid-19.

“In this time of fear and uncertainty, we are all working hard to help make sure everyone has accurate and necessary information. We are trying to help the people in our community by connecting them with facts. There is no reason to believe that DPE’s operations could contribute to an increased risk from Covid-19,” Harris said.

“State officials are reporting other factors may increase risks from the virus, including diabetes and obesity, both of which Louisiana has higher-than-average rates of,” Harris said.

The company’s words were little comfort to Robert Taylor. “The nature of the disease and our particular situation [with air pollution],” he said. “It makes this thing so frightening.”

Originally published at https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/apr/07/cancer-alley-coronavirus-reserve-louisiana

Photo by Andrew Gustar