The rapid spread of the novel coronavirus has many people wondering what environmental factors, beyond age and underlying health problems, make some individuals more vulnerable to COVID-19 than others.

That’s especially true in California, where residents have long struggled with the nation’s worst-polluted air.

So, does air pollution increase your risk?

Probably, experts say.

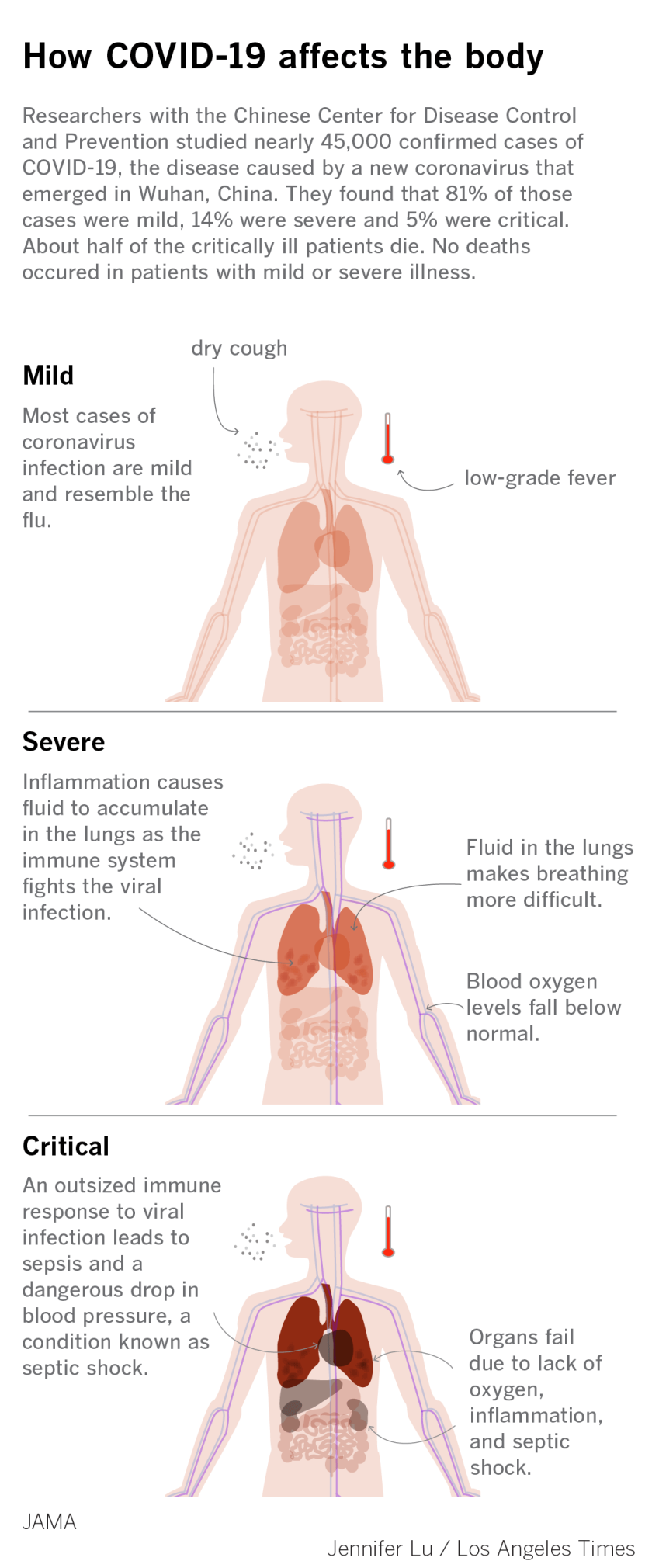

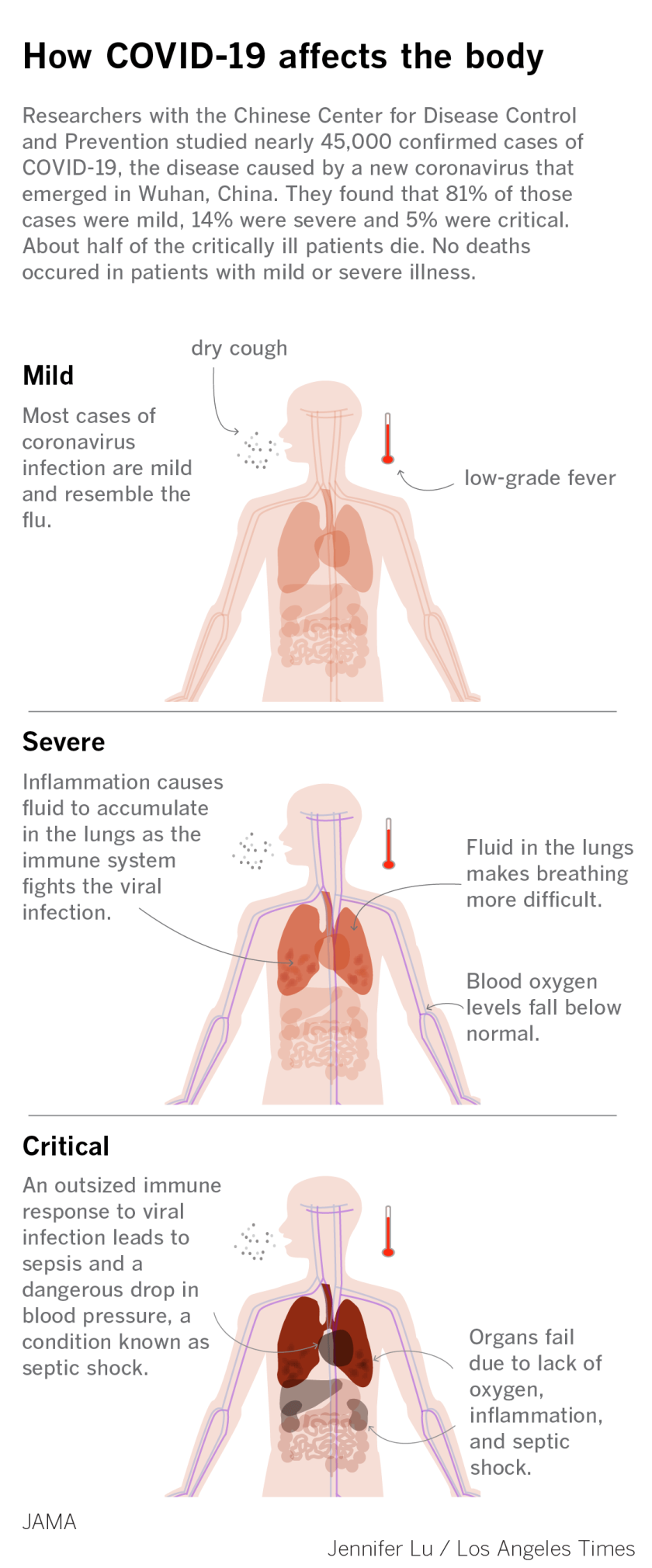

While health scientists can’t say for sure, they suspect bad air makes people more susceptible to the novel coronavirus. They point to loads of research showing people who smoke or breathe dirty air are at higher risk of contracting pneumonia caused by similar viruses and of developing more severe symptoms once they have it.

“There’s lots of evidence that air pollution increases the chances that someone will get pneumonia, and if they get pneumonia, will be sicker with it,” said Aaron Bernstein, interim director of the Center for Climate, Health, and the Global Environment at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. “We don’t have direct evidence of that with COVID, but I would be surprised if air pollution did not affect risk for COVID infection and the severity of illness.”

“The overwhelming majority of studies demonstrate that air pollution matters a lot to whether you are going to get sick with pneumonia and whether you are going to have mild illness or severe illness,” Bernstein added.

That means the virus could be more damaging to people living in polluted areas, because their lungs may already be impaired and their defenses weakened.

There is also evidence from previous outbreaks of similar coronaviruses that people exposed to dirty air are at greater risk of dying. Scientists who studied the SARS coronavirus outbreak in 2003 found that infected patients from regions with higher air pollution were 84% more likely to die than those in less-polluted areas.

Why do scientists suspect this?

Studies going back more than a decade have established that people living in neighborhoods with dirty air from vehicle exhaust and other combustion sources are hospitalized for pneumonia at higher rates than in areas with lower pollution, according to health experts.

That evidence indicates that long-term exposure to pollution makes people more susceptible to acquiring pneumonia in the first place and worsens their symptoms once they have it. It applies both to bacterial infections and those caused by viruses similar to the coronavirus.

“To the extent that it’s behaving like another pneumonia, yes, I think there’s going to be some elevated risk that’s associated with being in higher air pollution, but we don’t know enough about the biology of this particular virus to know how it’s going to respond,” said Michael Jerrett, a professor of environmental health science at the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health.

How does air pollution weaken our defenses?

People who live in smoggy areas may be less equipped to fight off the virus to begin with. That’s because air pollution, just like smoking, damages the lungs and makes it harder for them to fight off respiratory infections. Exposure to ozone, fine particulate matter and other components of smog stress and inflame the lungs over the long term.

“When a pollutant enters the lung, the lung treats it like a foreign invader and initiates a whole process of defense,” Jerrett said.

Cells try to remove the pollutant, he said, and over time that depletes energy, causing the lungs to become inflamed.

“Once the lung is inflamed, the ability of a virus to penetrate is elevated,” Jerrett said.

That affects the lungs’ response to a virus in the alveoli, the tiny air sacs where oxygen moves into the bloodstream.

“They’re already expending energy to fight air pollution,” Jerrett said. “If another invader comes in, their defense is already diminished.”

What if air quality improves in the short term?

There is robust evidence that even short-term exposure to polluted air can increase lung infections, Jerrett said. Meaning that when pollution goes up, hospitals see an increase in admissions for pneumonia a few days later.

“In that case it’s probably not necessarily contributing to the formation of the disease, but it is exacerbating the severity,” Jerrett said.

But it suggests we also stand to gain an advantage against the virus by improving air quality.

Satellite imagery has revealed dramatic declines in air pollution during quarantines and lockdowns in Italy and China.

In parts of California, residents have already begun to comment on how clean the air has been in the last few days, though air quality officials said it remains unclear if this is due mostly to recent rains and winds that flush out pollution, or the sudden drop-off in motor vehicle traffic.

If improved air quality becomes a widespread side effect of the outbreak, it could be a boon during a trying time, bringing health benefits just when people need them most to fight off respiratory infection.

How big of a health problem is dirty air?

Globally, air pollution is the greatest environmental health threat, killing 7 million people each year, according to the World Health Organization. The primary mechanism of harm are fine particles that penetrate deep into the lungs and cause illnesses such as stroke, heart disease, lung cancer and respiratory infections including pneumonia.

Most of those deaths occur in developing countries in Asia and Africa where pollution levels remain dangerously high.

But thousands of Americans still die from polluted air each year, despite big improvements in air quality compared to decades ago. In the U.S., the health damage remains worst in California, with its large population exposed to the nation’s highest smog levels.

Experts note a big overlap between the populations most vulnerable during the coronavirus outbreak and those most harmed by dirty air. Unfortunately, that means some of the same underlying health problems that make people more vulnerable to air pollution, such as asthma, heart and lung disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder, also appear to be risk factors for the coronavirus.

What about smoking?

Preliminary research on the novel coronavirus outbreak in China suggests that smokers are more susceptible to infection. Men, who smoke at higher rates than women in that country, were more likely to die from the virus, scientists found.

“If you don’t have good reason to stop smoking already, this is a good reason,” Bernstein said. While a definitive link has not been established yet for the coronavirus, he said, smoking has increased risk for most every other respiratory infection studied.

How else can I lower my risk from pollution?

There are other steps you can take to improve your air quality, especially inside your home, where you are likely spending a lot of time during widespread closures and social distancing.

“Make sure that the air filter on your HVAC system is clean,” Bernstein said. High-efficiency air filters — those rated 13 or higher on the 16-point MERV scale — can help remove particles that could inflame your lungs and weaken their defenses.

Don’t have a central air system? Consider using a standalone air-cleaning device, which helps reduce particle pollution levels in individual rooms within your home. Make sure the model you choose is certified by California regulators.

You can also reduce air pollution inside your home by venting your kitchen stove to the outside, if possible.

“If people have gas cooktops in their homes and they have a vent, make sure to use it,” Bernstein said. “You want to do anything you can now to make your indoor air as good as possible.”

By TONY BARBOZA STAFF WRITER

MARCH 21, 2020

Originally published at: https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2020-03-21/coronavirus-air-pollution-health-risk