Wildfires raging in California, Oregon and Washington have led to some of the worst air quality in the world

Washington Post interviewed COEH Director Dr. Michael Jerrett for this piece.

SAN FRANCISCO — Every morning for the past few weeks, JoEllen Depakakibo has had a new kind of morning routine. She sets her alarm for 6 and opens the Environmental Protection Agency’s AirNow site on her phone. Newly fluent in the numbers of the air quality indexes, or the AQI, she checks the pollution levels compulsively throughout the day, waiting to make a difficult decision.

If the number passes 150, called “unhealthy” by the EPA, Depakakibo has her employees shut the main door and turn on a medical-grade air purifier inside Pinhole Coffee Shop, the cafe she opened here six years ago. If it passes 200, they close the cafe. She’s had to shut five times in recent weeks because of the smoke that has stubbornly settled over the city.

“I always check in with my staff to make sure they feel good about coming in. If they say they don’t, we won’t open,” Depakakibo said from her home in Oakland, where she and her wife had the windows closed and two air filters running to protect their newborn baby.

As record-setting wildfires continue to burn up and down the West Coast, the numbers are still hard to comprehend. More than 5 million acres burned. At least 33 people dead. One month of destruction.

Stemming from climate change and land management practices, the fires are also having a massive impact on people far from any actual flames. Massive plumes of smoke have converged and covered almost the entire western edge of the United States. It has drifted into the neighboring states of Nevada and Arizona, lowering air quality in some parts. And smoke has even blotted out the sun thousands of miles away in D.C.

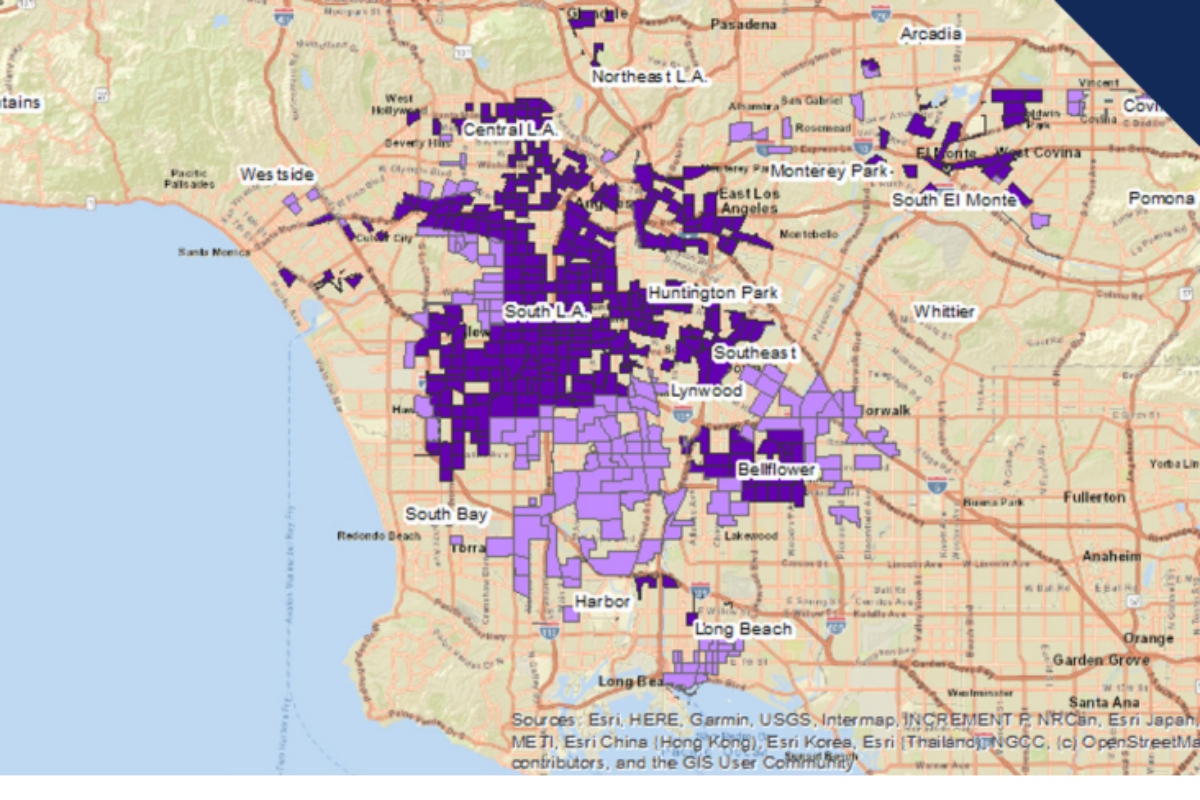

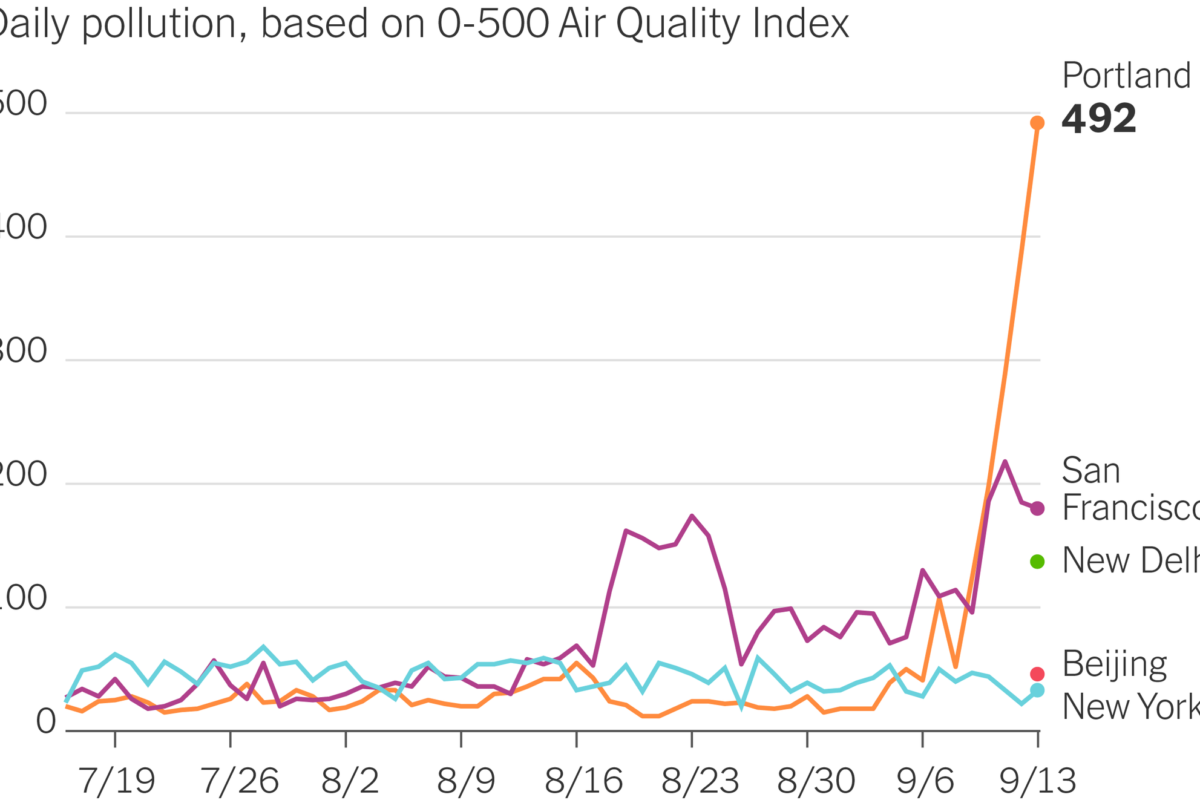

The haze along the West Coast has created the most polluted air in the world over the past week, forcing millions of residents indoors. The Bay Area has had a record run of bad air days, with residents being advised to avoid generating additional pollution for nearly a month. Air filters and purifiers have largely been sold out, and some people are buying personal air-quality devices to use in their homes. Some have put towels around their door frames and windows. Going outdoors is dangerous for even healthy lungs, and exercising has largely been out of the question.

Even if residents follow all precautions — a task made all the more difficult by coronavirus-related limitations on indoor activities — the smoke is still creating short- and long-term health risks for everyone exposed, health experts say.

The particles from wildfires are dangerously small, less than a micron wide, or 10 to 30 times smaller than the diameter of a human hair. Their size lets them slip past the body’s usual defenses and lodge deep inside the lungs, passing into the bloodstream and reaching the heart and the brain. The fires aren’t just burning trees but are also destroying houses, power lines and other infrastructure. The smoke is a complex mixture of volatile organic chemicals, ozone, nitrogen oxides and trace minerals, but it is the particulates less than 2.5 microns in size that worry experts the most.

Exposure can lead to immediate problems such as headaches, coughing and wheezing, and a person can become short of breath and experience a racing heartbeat. The dense smoke is a bigger danger for anyone with a respiratory ailment such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or asthma, and long-term exposure can contribute to heart attacks, strokes and, possibly, depression and anxiety, said Michael Jerrett, a professor at the Department of Environmental Health Sciences at the University of California at Los Angeles.

“At these levels, even healthy people will start feeling symptoms,” said Gopal Allada, an associate professor of medicine focusing on pulmonary and critical care at the Oregon Health & Science University School of Medicine in Portland.

The air in Portland was again the worst in the world on Wednesday, according to IQAir, which tracks air pollution levels globally. The EPA reported an AQI of 314 in the city as the Riverside Fire burned more than 135,000 acres in Oregon’s Clackamas County, roughly 50 miles away. Patients complaining of respiratory issues came into emergency rooms in the Portland area and sought help where they could find it.

On Monday, near downtown Portland, an aid group set up tents in the parking lot of the Lloyd Center mall. They handed out inhalers and masks. Medics treated irritated eyes.

One man showed up struggling to speak, his voice hoarse and his lips dusky. He told a medic, Tyler Cox, that he had COPD. Homeless, he had lost access to his nebulizer, a tool used for administering asthma medication.

Cox, an intensive care unit nurse volunteering in his free time, said he worried the temporary treatment might not be enough. “He could die if he’s in a place where he can’t get treatment,” Cox said in a voice made raspy by days of smoke exposure in the parking lot.

Victoria Olsen, another volunteer, said some people living on the streets have been tear-gassed by police in recent weeks amid the ongoing racial justice protests in the city.

“We have covid, we have the gas and then we have the smoke,” Olsen said.

Residents on the West Coast have for years dealt with the new realities of wildfire season, which tends to intensify in the fall when winds are high, the landscape is at its driest and before seasonal rains have begun. In November 2018, smoke from the deadly Camp Fire flowed into the Bay Area, causing people to stock up on N95 masks and air purifiers. Last year, the Kincade Fire in Sonoma County, just north of the Bay Area, triggered the same behavior.

It has become an annual event for residents in California, Oregon and Washington state: a week or two of smoke associated with a raging fire. Many already have some supplies and know what to do from past years.

This year is more difficult in many ways. Fire season came earlier than usual after an unusual lightning storm sparked many of the fires in California in mid-August. The blazes are also more widespread. At least 25 fires are burning in California and 29 in Oregon, according to officials. The pandemic has added complications, with breathable indoor spaces like offices, malls or movie theaters still largely off-limits.

And the smoke is lingering longer than usual — with more than a month of wildfire season to go.

Eight and a half months pregnant, Stephanie Sundstrom spends much of her time checking the EPA’s site and figuring out the best way to breathe clean air. To try to slow the toxic smoke leaking into her 110-year-old Portland house, she used duct tape to seal up a drafty back door. Aside from attending medical appointments, she tries to stay closed up in her bedroom, where a homemade air filter runs around-the-clock.

“I really want this to clear up before she gets here, because nobody wants their baby born in a smoky apocalypse,” said Sundstrom, 29, who works in marketing at Hewlett-Packard. “It just feels so unescapable; there’s nothing you can do. You can try to stay in your house, but everything just smells smoky.”

Like Sundstrom, many residents here monitor the air quality as they once did the weather. When deciding whether to go outside, they look up pollution levels for the locations around them on sites and apps like PurpleAir, AirVisual and AirNow. The maps show color-coded air-quality levels, pulled from government or low-cost sensors, typically ranging from “good” green to “hazardous” maroon.

PurpleAir is a Utah-based company that uses data from low-cost sensors it sells to map out air quality, and shares the data with other companies to map. The company has experienced a 1,000 percent increase in visitors to its website since the fires began, according to founder and CEO Adrian Dybwad, and has had a surge in orders for the air-quality sensors it sells. Air-quality apps have topped the download charts for weather over the past week, while traditional weather forecasts have added AQI numbers alongside temperature and humidity.

Read the rest of the article at https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2020/09/16/smoke-air-west/

By Heather Kelly and Samantha Schmidt

Originally published September 16, 2020